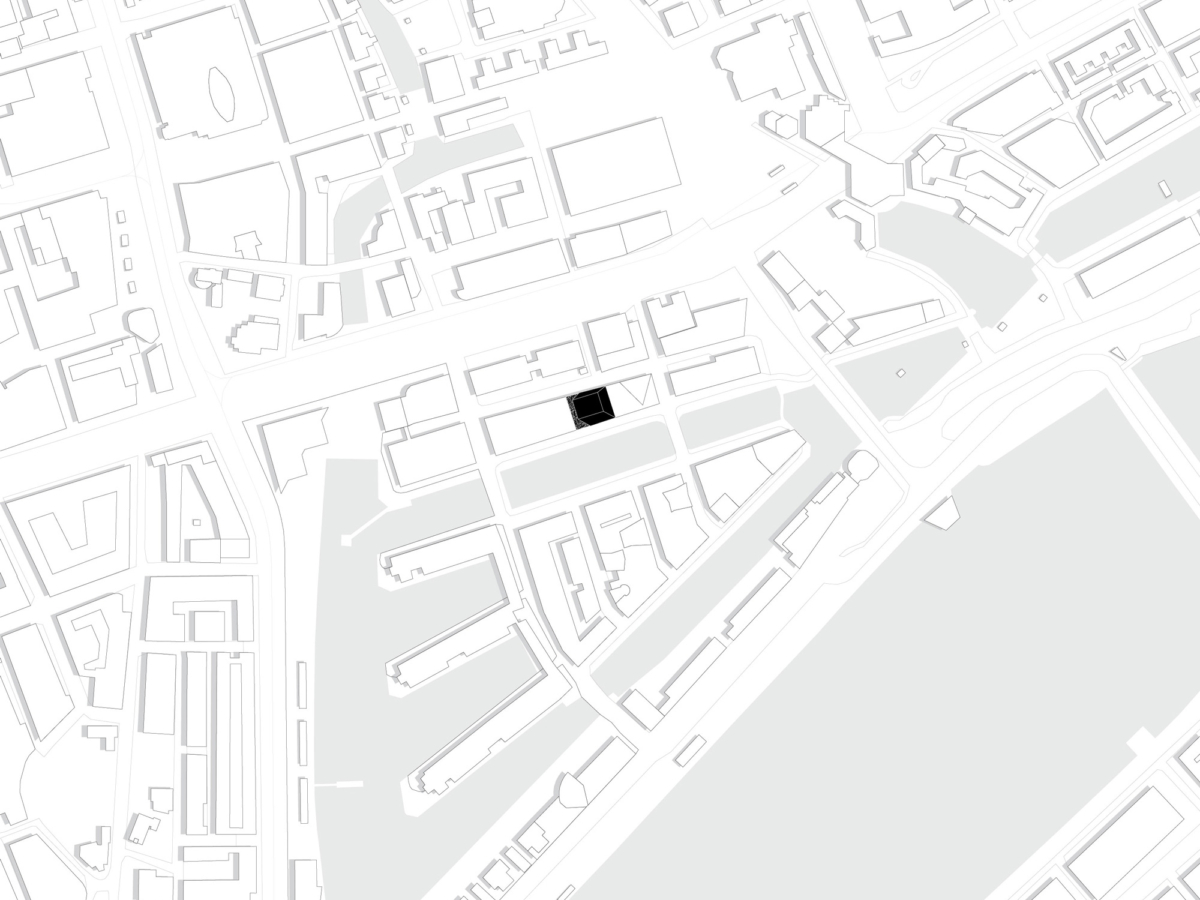

The ‘Gele Scheikunde’ site holds a significant historical legacy and stands out by its distinct architectural style, which is characterised by a typical yellow brick and the use of interlocking volumes that break down the scale of the large complex.

When we were tasked to transform and repurpose this site, we took it as our challenge to use this language. To create balance between preserving the site’s unique character and ensuring that it harmoniously integrates with both the small-scale of the immediate surroundings and the larger urban context of the university district.

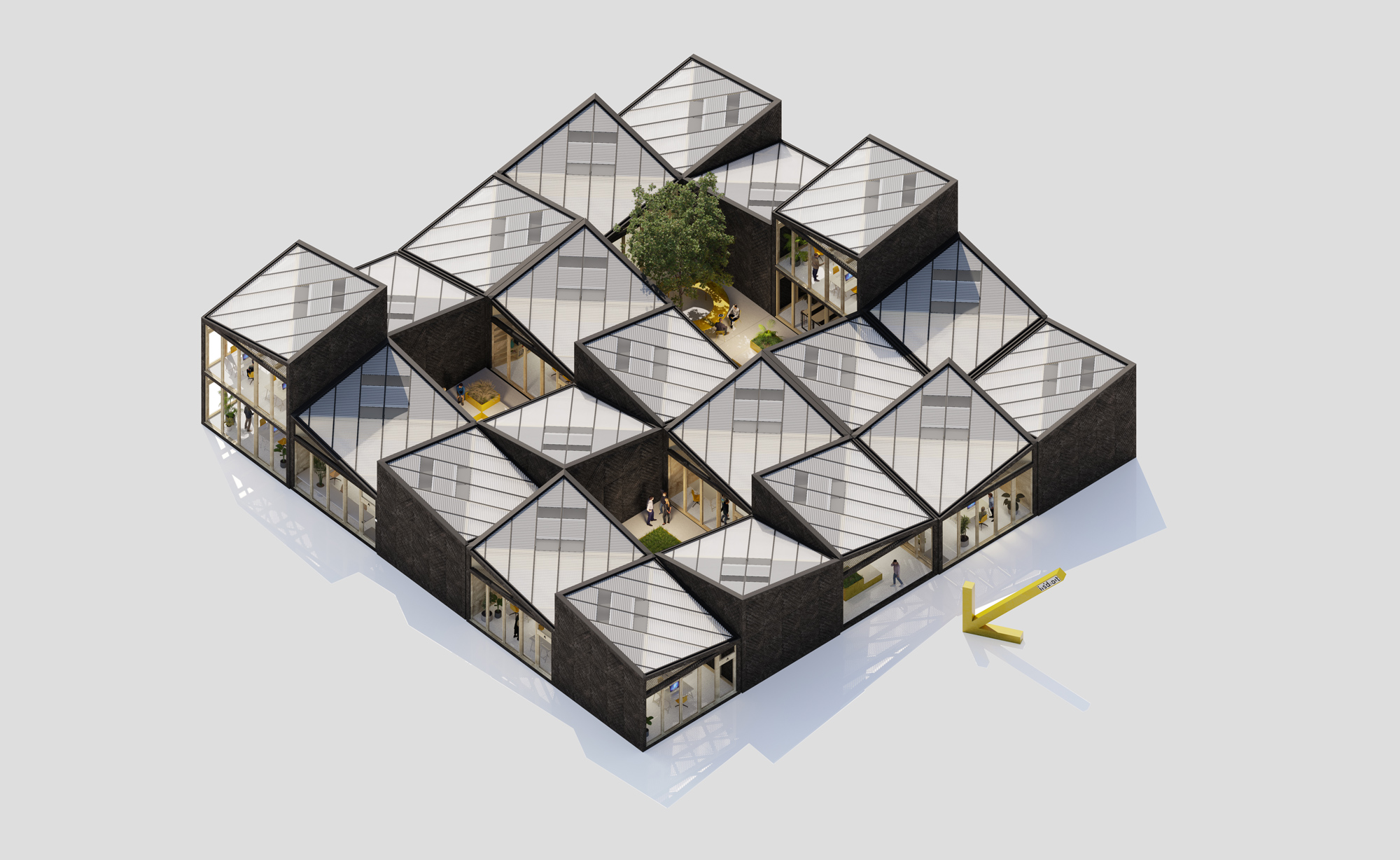

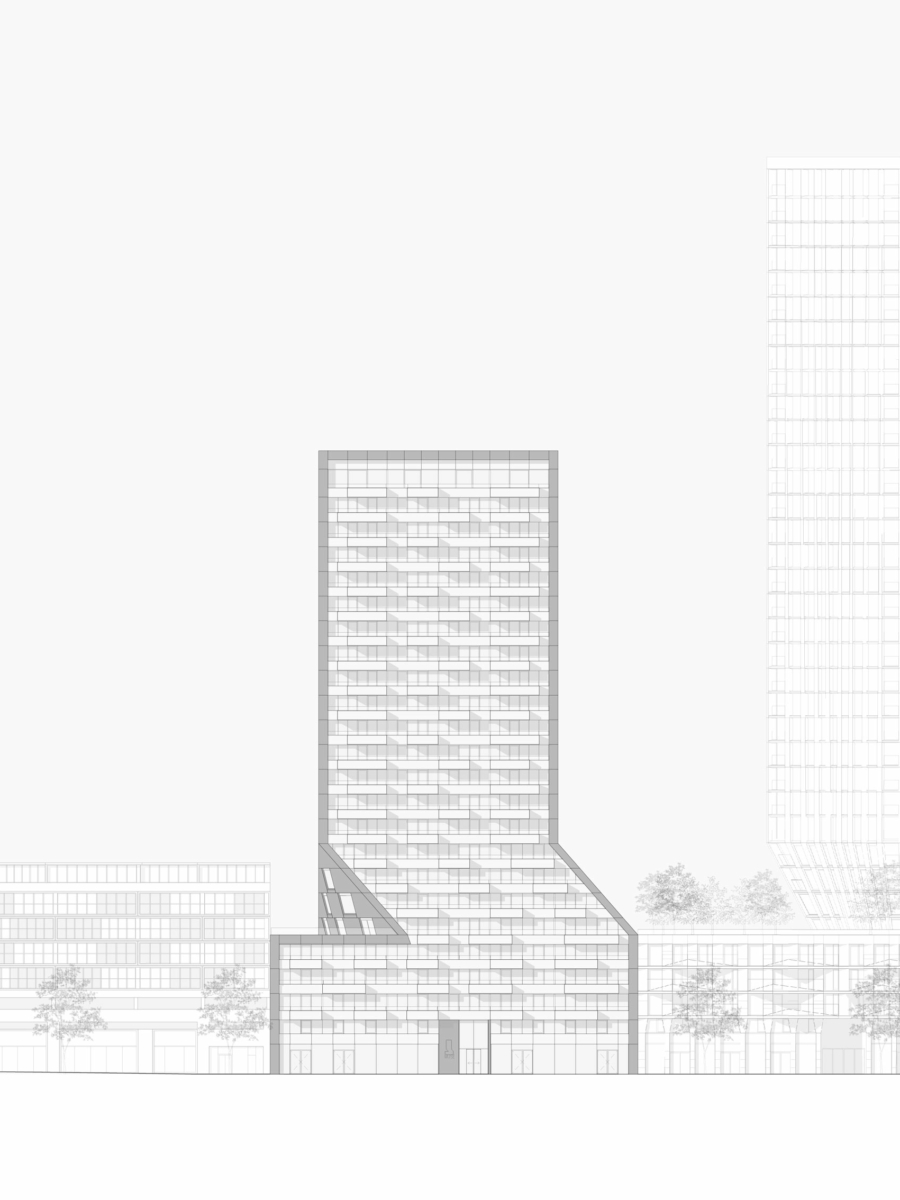

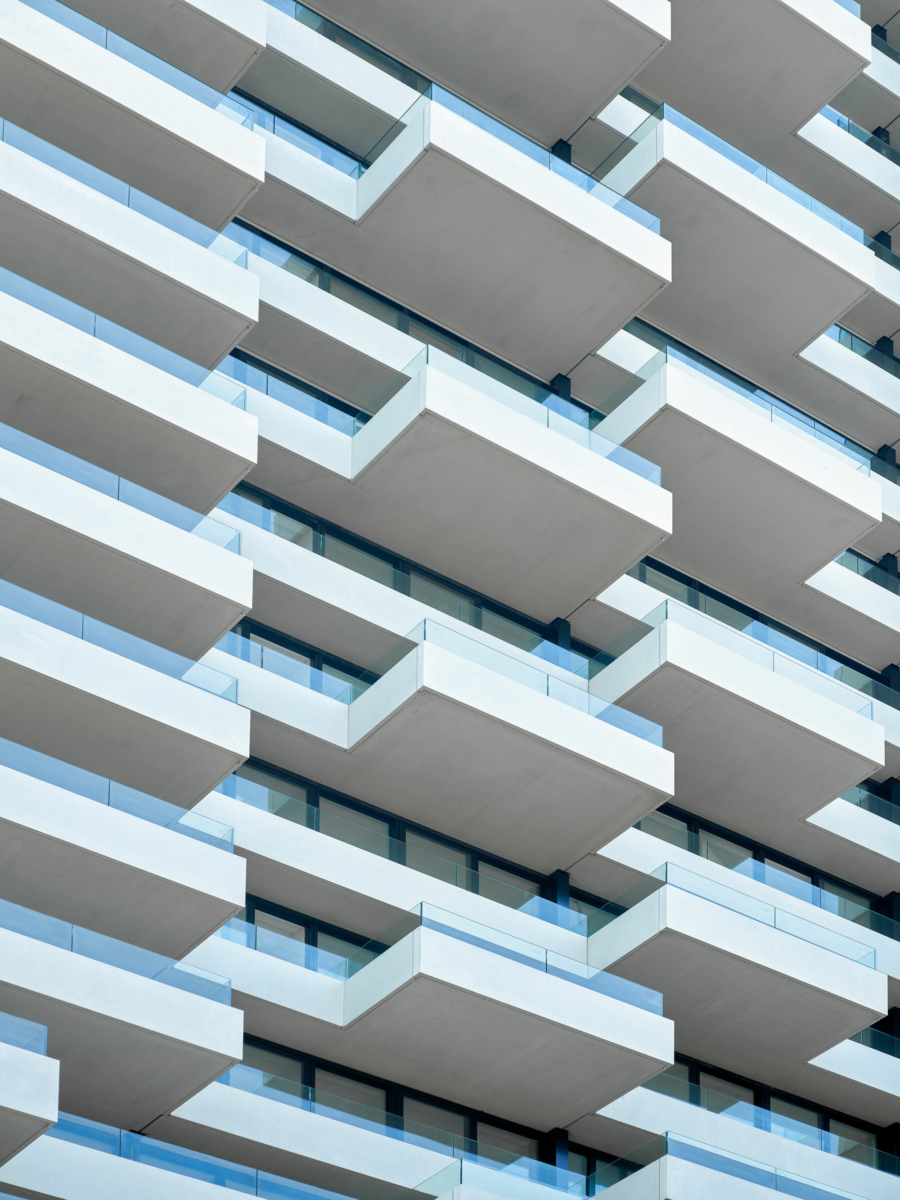

The resulting design exhibits three distinctive aspects. Firstly, we selected the historic buildings which will undergo complete transformation. We accentuated their rich historical significance and combined this with new qualities. Secondly, we introduced a cluster of ground-level houses in a characteristic urban housing style, which aligns seamlessly with the Juliana neighbourhood. Lastly, we incorporated several high-rise blocks that bridge the gap between the intimate scale of the city centre and the expansive scope of the TU district. These larger elements deliberately employ the language of interlocking, providing them with an invitingly varied scale and allowing them to be big and be small.

The ‘Gele Scheikunde’ complex’s overall atmosphere is elevated through the incorporation of a green collar and the consistent use of a harmonious material and colour scheme. Additionally, we have introduced delicate architectural elements at points where people come in contact with the buildings, further enriching the sense of location.